The Canadian Human Rights Act, created in 1977, is designed to ensure equality of opportunity. It prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, age, sex and a variety of other categories. The Act produced two human rights bodies: the Canadian Human Rights Commission and, through a 1985 amendment, the Human Rights Tribunal Panel (it became the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal in 1998). Decisions of both the Commission and the Tribunal can be appealed to the Federal Court of Canada. Unlike the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which provides Canadians with a broad range of rights, the Canadian Human Rights Act covers only equality rights. It also governs only federal jurisdictions. Each province and territory in Canada has its own human rights legislation, which apply to local entities such as schools and hospitals.

Following the Second World War, leaders in Canada and around the world recognized the importance of introducing explicit human rights protections. They adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights at the General Assembly of the newly formed United Nations (UN) in 1948. The declaration was drafted by Canadian John Humphrey and Eleanor Roosevelt. (See also Editorial: John Humphrey, Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.)

With the Racial Discrimination Act in 1944, Ontario became the first jurisdiction in Canada to pass legislation solely dedicated to anti-discrimination. In 1947, Saskatchewan passed the Saskatchewan Bill of Rights. Canada’s first bill of rights, it protected traditional democratic civil liberties such as speech, assembly, religion, association and due process. It also prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, religion and national origin. Similar acts were passed across the country. Canadian lawmakers then began to consider a federal law to create equal opportunities by prohibiting discrimination. In 1960, Parliament moved in this direction with the passage of the Canadian Bill of Rights. It protected freedom of speech, freedom of religion and equality rights, among others.

Eleanor Roosevelt holding the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Lake Success, 1949. Canadian John Humphrey was the principal author. (courtesy US National Archives/6120927)

Over the next two decades, lawmakers across Canada started to create comprehensive human rights regimes that consolidated existing laws. In 1962, Ontario passed the Human Rights Code. It brought together a series of human rights laws that were already on the books. The Human Rights Code also created the Ontario Human Rights Commission. It was designed to prevent, educate and enforce human rights across the province.

In the years that followed, other jurisdictions across the country introduced similar pieces of legislation. This cross-Canada development coincided with the growing prominence of social movements. These movements sought to advance issues such as racial justice and women’s rights at home and abroad. (See also Rights Revolution in Canada; Women’s Movements in Canada; Disability Rights Movement in Canada.)

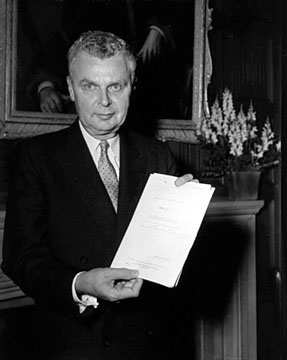

Prime Minister Diefenbaker displaying the Bill of Rights of 1958. (D. Cameron/National Archives of Canada/PA-112659)

Parliament introduced the Canadian Human Rights Act in 1977; more than three decades after the creation of the first standalone human rights laws in Canada. Most people agreed in principle with the passage of the Canadian Human Rights Act. However, many disagreed on a range of issues; these included which categories should be protected and how human rights violations should be remedied. When it was introduced in 1977, the legislation not only prohibited discrimination on the basis of well-established grounds such as race, religion and national origin; it also included relatively newer grounds such as sex, ethnic origin, age, marital status, physical disability and pardoned conviction. Over time, the Canadian Human Rights Act was amended to add sexual orientation (1996) and gender identity or expression (2017) as protected categories. (See LGBTQ2 Rights in Canada.)

The Canadian Human Rights Act applies only to people who work for or receive benefits from the federal government; to First Nations; and to federally regulated private companies such as airlines and banks. Each province and territory in Canada has its own human rights legislation, which apply to local entities such as schools and hospitals.

The Canadian Human Rights ;Act contains three main parts: (I) Proscribed Discrimination; (II) the Canadian Human Rights Commission; and (III) Discriminatory Practices and General Provisions.

The purpose of the Canadian Human Rights Act ;is to ensure that all individuals have “opportunity equal with other individuals to make for themselves the lives that they are able and wish to have and to have their needs accommodated, consistent with their duties and obligations as members of society, without being hindered in or prevented from doing so by discriminatory practices.” The Act sets out 13 prohibited grounds of discrimination: “race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, marital status, family status, genetic characteristics, disability, and conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted or in respect of which a record suspension has been ordered.”

Part I lays out a series of interconnected human rights concepts; these include discrimination, harassment, and bona fide justification. Discrimination is not expressly defined in the Canadian Human Rights Act. It generally refers to the unfair treatment of a person on the basis of one or more of the prohibited grounds of discrimination. The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination in a variety of contexts, including:

The Canadian Human Rights Act also prohibits harassment. While the Act does not expressly define the concept, harassment includes, but it is not limited to, unwelcome remarks or unwanted touching. A practice will not be found to be discriminatory if there is a bona fide justification.

Until 2013, the Canadian Human Rights Act also prohibited the communication of hate messages; these were defined as “any matter that is likely to expose a person or persons to hatred or contempt by reason of the fact that that person or those persons are identifiable on the basis of a prohibited ground of discrimination.” (See also Hate Propaganda.) There were a series of high-profile controversies and constitutional challenges. The federal government then repealed the hate messages provision of the Canadian Human Rights Act in 2013.

Part II created the Canadian Human Rights Commission. It is responsible for human rights education, prevention and investigation. It sets out the Commission’s powers, duties and functions. It also describes the process for appointing its members.

Part III contains a series of additional definitions, along with general provisions. For example, it lays out the process that should be followed when parties decide to enter into a settlement agreement. Part III also created the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal and describes the process for appointing its members. The tribunal is responsible for adjudicating claims of discrimination. (See also Administrative Tribunals in Canada.)

Since its inception in 1977, the Canadian Human Rights Act has produced a series of landmark human rights rulings. They have occurred in such areas as women’s rights, LGBTQ2 rights, and Indigenous rights. An example of each of these are as follows.

In this 1989 women’s rights case, three women successfully challenged the Canadian Armed Forces’ policy of excluding women from certain roles, including combat. They argued that the differential treatment between women and men constituted discrimination on the basis of sex. Today, women are eligible to serve in any role within the Canadian Armed Forces.

In 1992, Captain Joshua Birch launched a human rights complaint after being discharged from the Canadian Forces for disclosing he was gay. He successfully argued that the omission of sexual orientation from the Canadian Human Rights Act constituted discrimination under the equality rights guarantee set out in section 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. To remedy this, the Ontario Court of Appeal read the term sexual orientation into the Canadian Human Rights Act. In 1996, Parliament formally added sexual orientation as a protected ground in the Act.

In 2016, the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada successfully argued that the Canadian government’s provision of child and family services to First Nations on reserve and in Yukon constituted discrimination by failing to provide the same level of services that exist elsewhere in Canada. The decision promises to have enormous implications for Indigenous rights in Canada.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms was entrenched in the Constitution of Canada in 1982. (See Constitution Act, 1982.) This was just five years after the Canadian Human Rights Act was enacted. While the two documents are comparable, they differ in a few key areas. As part of the Constitution, the Charter is the highest law of the land. It can only be changed with the agreement of Parliament and the legislatures of seven provinces representing at least 50 per cent of Canada’s population. The Canadian Human Rights Act, on the other hand, is a federal statute. As such, it can be changed through parliamentary vote; this was the case in 2013, when the federal government repealed the hate messages provision of the Act. The Charter provides Canadians with a broad range of rights; these include democratic, legal, language and equality rights at all levels of government. The ;Canadian Human Rights Act covers only equality rights, including the prohibition of discrimination. It also governs only federal jurisdictions.

Copy of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. (Dept of Secretary of State, Canada)